SOLVING PARTIAL DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS BY FACTORING

vertex and slope of linear equation,

adding subtracting dividing multiplying scientific notation worksheet,

vertex and slope of linear graph ,

TI89 quadratic equation solver method

Thank you for visiting our site! You landed on this page because you entered a search term similar to this: solving partial differential equations by factoring.

We have an extensive database of resources on solving partial differential equations by factoring. Below is one of them. If you need further help, please take a look at our software "Algebrator", a software program that can solve any algebra problem you enter!

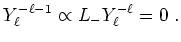

One will see that the very existence of the eigenvalue spectrum of

on the unit sphere hinges on this fact.

For this reason, the extension of this algebraic method is considerably more

powerful. It yields not only the basis for each eigenspace of on the unit sphere hinges on this fact.

For this reason, the extension of this algebraic method is considerably more

powerful. It yields not only the basis for each eigenspace of

, but also the actual value for each allowed degenerate

eigenvalue. , but also the actual value for each allowed degenerate

eigenvalue.

Global Analysis: Algebra

Global analysis deals with the solutions of a differential equation

``wholesale''. It characterizes them in relationship to one another

without specifying their individual behaviour on their domain of

definition. Thus one focusses via algebra, linear or otherwise, on

``the space of solutions'', its subspaces, bases etc.

Local analysis (next subsubsection), by contrast, deals with the solutions

of a differential equation ``retail''. Using differential calculus,

numerical analysis, one zooms in on individual functions and characterizes

them by their local values, slopes, location of zeroes, etc.

1. Factorization

The algebraic method depends on factoring

into a pair of first order operators which are adjoints of each other.

The method is analogous to factoring a quadratic polynomial, except

that here one has differential operators

and

and

instead of the variables instead of the variables  and and  .

Taking our cue from Properties 16 and 17, one attempts

However, one immediately finds that this factorization yields .

Taking our cue from Properties 16 and 17, one attempts

However, one immediately finds that this factorization yields

for a cross

term. This is incorrect. What one needs instead is for a cross

term. This is incorrect. What one needs instead is

. This

leads us to consider . This

leads us to consider

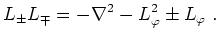

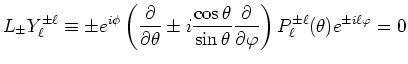

Here we have introduced the self-adjoint operator

It generates rotations around the polar axis of a sphere. This operator,

together with the two mutually adjoint operators

are of fundamental importance to the factorization method of solving

the given differential equation. In terms of them the factorized

Eq.(5.135) and its complex conjugate have the form

|

(5136) |

This differs from Eq.(5.16),

(Property 17 on page ), the

factored Laplacian on the Euclidean plane.

2. Fundamental Relations

In spite of this

difference, the commutation relations corresponding to

Eqs.() are all the same, except one. Thus, instead

of Eq.(5.19), for a sphere one has

![$\displaystyle [L_+,L_-]=2L_\varphi~.$](img3906_1.png) |

(5137) |

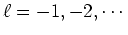

This is obtained by subtracting the two

Eqs.(5.136). However, the commutation

relations corresponding to

the other two equations remain the same. Indeed, a little algebraic

computation yields

or

![$\displaystyle [L_\varphi, L_\pm]= \pm L_\pm ~.$](img3908_1.png) |

(5138) |

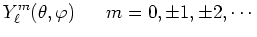

Furthermore, using Eq.(5.136) one finds

The last equality was obtained with the help of

Eqs.(5.137) and (5.138).

Together with the complex conjugate of this equation, one has therefore

![$\displaystyle [\nabla^2,L_\pm]=0~.$](img3915_1.png) |

(5140) |

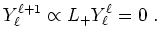

In addition, one has quite trivially

![$\displaystyle [\nabla^2,L_\varphi]=0$](img3916_1.png) |

(5141) |

The three algebraic relations,

Eqs.(5.137)-(5.138)

and their consequences,

Eq.(5.140)-(5.141), are the

fundamental equations from which one deduces the allowed degenerate

eigenvalues of Eq.(5.132)

as well as the corresponding normalized eigenfunctions.

3. The Eigenfunctions

One starts by considering a function

which is a simultaneous

solution to the two eigenvalue equations which is a simultaneous

solution to the two eigenvalue equations

This is a consistent system, and it is best to postpone until later

the easy task of actually exhibiting non-zero solutions to it. First

we deduce three properties of any given solution

. .

The first property is obtained by applying the operator  to this solution. One finds that

to this solution. One finds that

Similarly one finds

Thus

and and

are again eigenfunctions of are again eigenfunctions of

, but having eigenvalues , but having eigenvalues  and and  . One is, therefore,

justified in calling . One is, therefore,

justified in calling  and and  raising and

lowering operators.

The ``raised'' and ``lowered'' functions raising and

lowering operators.

The ``raised'' and ``lowered'' functions

have the additional property that they are still

eigenfunctions of have the additional property that they are still

eigenfunctions of  belonging to the same eigenvalue belonging to the same eigenvalue  .

Indeed, with the help of Eq.(5.140) one finds

Thus, if .

Indeed, with the help of Eq.(5.140) one finds

Thus, if

belongs to the eigenspace of belongs to the eigenspace of  ,

then so do ,

then so do

and and

. .

4. Normalization and the Eigenvalues

The second and third properties concern the normalization of

and the allowed values of and the allowed values of  .

One obtains them by examining the sequence of squared norms

of the sequence of eigenfunctions .

One obtains them by examining the sequence of squared norms

of the sequence of eigenfunctions

All of them are square-integrable. Hence their norms are non-negative.

In particular, for  one has one has

This is the second property. It is a powerful result for two reasons:

First of all, if

has been normalized to unity, then so

will be has been normalized to unity, then so

will be

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{[\lambda - m(m\pm 1)]^{1/2}} L_\pm Y_\lambda^m(\theta,\varphi) \equiv Y_\lambda^{m\pm 1}(\theta,\varphi)$](img3941_1.png) |

(5143) |

This means that once the normalization integral has been worked out

for any one of the

's, the already normalized 's, the already normalized

are given by

Eq.(5.143); no additional

normalization integrals need to be evaluated. By repeatedly applying

the operator are given by

Eq.(5.143); no additional

normalization integrals need to be evaluated. By repeatedly applying

the operator  one can extend this result to one can extend this result to

, ,

, etc. They all are already normalized if , etc. They all are already normalized if

is. No extra work is necessary. is. No extra work is necessary.

Secondly, repeated use of the relation (5.142)

yields

This relation implies that for sufficiently large integer  the

leading factor in square brackets must vanish. If it did not, the

squared norm of the

leading factor in square brackets must vanish. If it did not, the

squared norm of

would become negative. To

prevent this from happening, would become negative. To

prevent this from happening,  must have very special values.

This is the third property: The only allowed values of must have very special values.

This is the third property: The only allowed values of  are

necessarily

(Note that are

necessarily

(Note that

would give nothing new.) Any other

value for would give nothing new.) Any other

value for  would yield a contradiction, namely a negative

norm for some integer would yield a contradiction, namely a negative

norm for some integer  . As a consequence, one has the result

that for each allowed eigenvalue there is a

sequence of eigenfunctions . As a consequence, one has the result

that for each allowed eigenvalue there is a

sequence of eigenfunctions

|

(5144) |

(Nota bene: Note that these eigenfunctions are now labelled by

the non-negative integer  instead of the corresponding

eigenvalue instead of the corresponding

eigenvalue  .) Of particular interest are the two

eigenfunctions .) Of particular interest are the two

eigenfunctions

and and

. The squared norm of . The squared norm of

,

is not positive. It vanishes. This implies that ,

is not positive. It vanishes. This implies that

|

(5145) |

In other words,

and all subsequent members of the

above sequence, Eq.(5.144) vanish, i.e.

they do not exist. Similarly one finds that and all subsequent members of the

above sequence, Eq.(5.144) vanish, i.e.

they do not exist. Similarly one finds that

|

(5146) |

Thus members of the sequence below

do not exist either.

It follows that the sequence of eigenfunctions corresponding to do not exist either.

It follows that the sequence of eigenfunctions corresponding to

is finite. The sequence has only is finite. The sequence has only  members, namely

for each integer members, namely

for each integer  . The union of these sequences forms a semi-infinite

lattice in the . The union of these sequences forms a semi-infinite

lattice in the  as shown in

Figure 5.21. as shown in

Figure 5.21.

Figure 5.21:

Lattice of eigenfunctions (spherical hamonics) labelled

by the angular integers  and and  . Application of the raising operator . Application of the raising operator

increases increases  by by  , until one comes to the top of each

vertical sequence (fixed , until one comes to the top of each

vertical sequence (fixed  ). The lowering operator ). The lowering operator

decreases decreases  by by  , until one reaches the bottom.

In between there are exactly , until one reaches the bottom.

In between there are exactly  lattice points, which express

the ( lattice points, which express

the ( )-fold degeneracy of the eigenvalue )-fold degeneracy of the eigenvalue

.

There do not exist any harmonics above or below

the dashed boundaries. .

There do not exist any harmonics above or below

the dashed boundaries.

|

For obvious reasons it is appropriate to

refer to this sequence as a ladder with  elements, and

to call elements, and

to call

the top, and the top, and

the

bottom of the ladder. The raising and lowering operators the

bottom of the ladder. The raising and lowering operators

are the ladder operators which take us up and down the are the ladder operators which take us up and down the

-element ladder. It is easy to determine the elements -element ladder. It is easy to determine the elements

at the top and the bottom, and to use the ladder

operators to generate any element in between. at the top and the bottom, and to use the ladder

operators to generate any element in between.

5. Orthonormality and Completeness

The operators

form a complete set of commuting

operators.

This means that their eigenvalues form a complete set of commuting

operators.

This means that their eigenvalues  serve as sufficient labels to uniquely identify each of

their (common) eigenbasis elements for the vector space of solutions

to the Hermholtz equation

serve as sufficient labels to uniquely identify each of

their (common) eigenbasis elements for the vector space of solutions

to the Hermholtz equation

on the two-sphere. No additional labels are necessary. The fact that

these operators are self-adjoint relative to the inner product,

Eq.(5.134), implies that these

eigenvectors (a.k.a spherical harmonics) are orthonormal:

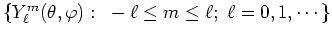

The semi-infinite set

is a basis for the vector space of functions

square-integrable on the unit two-sphere. Let is a basis for the vector space of functions

square-integrable on the unit two-sphere. Let

be

any such function. Then be

any such function. Then

In other words, the spherical harmonics are the basis elements for a

generalized double Fourier series representation of the function

. If one leaves this function unspecified,

then this completeness relation can be restated in the equivalent

form

in terms of the Dirac delta functions on the compact domains . If one leaves this function unspecified,

then this completeness relation can be restated in the equivalent

form

in terms of the Dirac delta functions on the compact domains

and and

. .

Local Analysis: Calculus

What is the formula for a harmonics

?

An explicit functional form determines the graph, the location of its

zeroes, and other aspects of its local behaviour. ?

An explicit functional form determines the graph, the location of its

zeroes, and other aspects of its local behaviour.

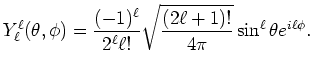

1. Spherical Harmonics: Top and Bottom of the Ladder

Each member of the ladder sequence satisfies the differential equation

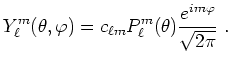

Consequently, all eigenfunctions have the form

|

(5147) |

Here

is a normalization factor.

The two eigenfunctions is a normalization factor.

The two eigenfunctions

and and

at the top and the bottom of the ladder satisfy Eqs.(5.145)

and (5.146) respectively, namely

at the top and the bottom of the ladder satisfy Eqs.(5.145)

and (5.146) respectively, namely

|

(5148) |

It is easy to see that their solutions are

The normalization condition

implies that

|

(5149) |

The phase factor  is not determined by the normalization.

Its form is chosen so as to simplify the to-be-derived formula for the

Legendre polynomials, Eq.(5.153). is not determined by the normalization.

Its form is chosen so as to simplify the to-be-derived formula for the

Legendre polynomials, Eq.(5.153).

2. Spherical harmonics: Legendre and Associated Legendre

polynomials

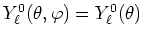

The functions

are obtained by applying the

lowering operator are obtained by applying the

lowering operator  to to

. A systematic

way of doing this is first to apply repeatedly the lowering relation . A systematic

way of doing this is first to apply repeatedly the lowering relation

to

until one obtains the azimuthally

invariant harmonic until one obtains the azimuthally

invariant harmonic

. Then

continue applying this lowering relation, or alternatively the raising

relation . Then

continue applying this lowering relation, or alternatively the raising

relation

until one obtains the desired harmionic

.

The execution of this two-step algorithm reads as follows: .

The execution of this two-step algorithm reads as follows:

Step 1: Letting

, apply Eq.(5.150) , apply Eq.(5.150)

times and obtain times and obtain

which, because of Eq.(5.147), is independent of

. Now let . Now let  , use Eq.(5.149),

and obtain , use Eq.(5.149),

and obtain

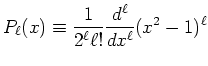

The polynomials in the variable

|

(5153) |

are called the Legendre polynomials. They have the property

that at the North pole they have the common value unity, while at the

South pole their value is  whenever whenever  is an even

polynomial and is an even

polynomial and  whenever it is odd:

Step 2: To obtain the harmonics having positive azimuthal integer whenever it is odd:

Step 2: To obtain the harmonics having positive azimuthal integer

, apply the raising operator , apply the raising operator   times to times to  . With the

help of Eq.(5.151) one obtains (for . With the

help of Eq.(5.151) one obtains (for

) )

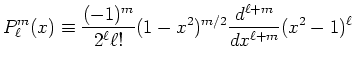

The polynomials in the variable

|

(5155) |

are called the associated Legendre polynomials.

Inserting Eq.(5.154) into

Eq.(5.132), one finds that they satisfy the differential equation

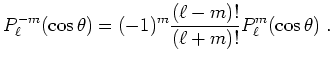

Also note that

satisfies the same differential

equation. In other words, satisfies the same differential

equation. In other words,

and and

must be

proportional to each other. (Why?) Indeed, must be

proportional to each other. (Why?) Indeed,

|

(5156) |

|